The Abbasid caliphate was the second of two prominent dynasties of the caliphate’s Muslim realm. It dissolved the Umayyad caliphate in 750 CE and ruled as the Abbasid caliphate until 1258 when it was overthrown by a Mongol invasion.

The term derives from the Prophet Muhammad’s uncle, al-Abbs (died c. 653) of the Hashemite clan of the Quraish in Makkah. From about 718, his immediate relatives tried to wrest leadership of the kingdom from the Umayyads and, using skilled propaganda, gained widespread support, particularly among Shii Arabs and Persians in Khorsn. Then under the supervision of Ab Muslim, another open uprising in 747 culminated in the downfall of Marwan II, the final Umayyad caliph, at the Battle of the Great Zab River (750) in Mesopotamia and the declaration of the first Abbasid caliph, Ab al-Abbs al-Saff.

Foundation of Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasids differentiated themselves from the Umayyads by criticising their character and integrity and overall government. The Abbasids also courted non-Arab Muslims known as mawali, who stayed outside the Arabs’ kinship-based culture and were viewed as an inferior class inside the Umayyad realm. During the rule of Umar II, Muhammad ibn ‘Ali, Abbas’ great-grandson, started to campaign in Persia for the restoration of power to Muhammad’s family, the Hashemites.

This resistance resulted in the uprising of Ibrahim al-Imam, the fourth in line from Abbas, during the rule of Marwan II. He gained tremendous success with the help of the region of Khorasan (Eastern Persia), despite the governor’s opposition, and the Shia Arabs, but was arrested in 747 and died, presumably killed, in jail. On June 9, 747 (15 Ramadan 129), Abu Muslim, rising from Khorasan, successfully launched an open uprising against Umayyad power under the banner of the Black Standard. So when the fighting started in Merv, Abu Muslim was in charge of about 10,000 warriors. General Qahtaba pursued the retreating governor Nasr ibn Sayyar west, conquering the Umayyads in the Battles of Gorgan, Nahvand, and Karbala, all in the year 748.

The dispute was taken up by Ibrahim’s brother Abdallah, known as Abu al-‘Abbas as-Saffah, who beat the Umayyads in the fight near the Great Zab in 750 and was later declared caliph. Marwan went to Egypt after this defeat, where he was assassinated. Except for one man, the rest of his family was likewise killed. As-Saffah immediately moved his soldiers to Central Asia, where they battled the opposing Tang invasion during the Battle of Talas. The aristocratic Iranian family Barmakids, who were involved in the construction of Baghdad, established the city’s first known paper mill, ushering in a new period of cultural regeneration in the Abbasid empire. As-Saffah concentrated on suppressing many rebellions in Syria and Mesopotamia. Throughout these early diversions, the Byzantines undertook attacks.

The Beginning of Abbasid Rule

After his victory at As-Saffah, he quickly dispatched the majority of his forces to Central Asia to block the Chinese Tang Dynasty’s advancement – their progress was interrupted at the battles of Talas (751 CE) when the Muslims suffered a crushing loss. However, friendly ties quickly followed this short period of bloodshed, bringing about a new era in Islamic history when, instead of expanding, the Abbasids chose to gratify and protect what they already had.

As-Saffah exacted revenge on the Umayyads, without sparing the life of the dead. Umayyad cemeteries in Syria were dug up, their bones ripped and burned, and all live male members were slaughtered. Those who fled into hiding to avoid such a horrifying death were enticed out with a celebratory dinner and assurances of security and peace, only to be wickedly slaughtered in front of the governing party, whose members proceeded to feast unmoved to the groans of their dying victims.

Read More...

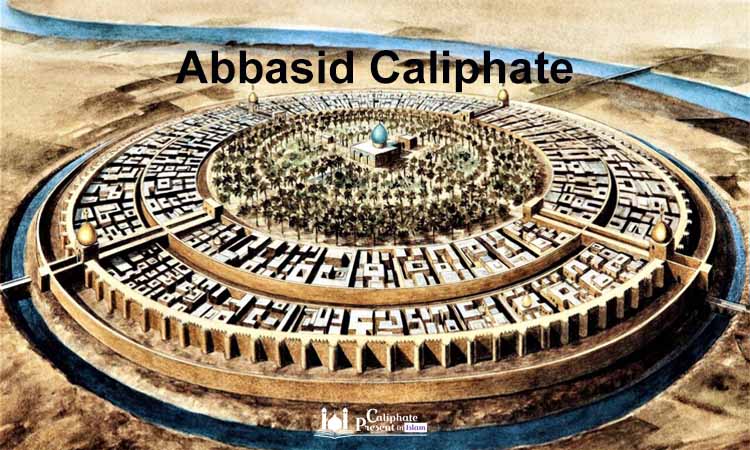

Baghdad & Al-Mansur (750–754)

Al-Mansur, like his brother, committed crimes, and this time the family of Abbas poured its fury on Ali’s successors. He pushed them to mutiny, believing they were plotting against him, and then suppressed the insurrection (762-763 CE) with severe severity. Due to his growing authority, Abu Muslim (d. 755 CE), the man who established the Abbasid Dynasty, became his target; the disfigured corpse of his house’s recipient was unceremoniously tossed in the Tigris River.

Both As Saffah’s and Al- Mansur’s brutality to their rivals crossed all lines of decency; those who had previously thought of the Umayyads as demonic monsters who would fan the fires of hell felt empathetic to the family. Al-Mansur was a great diplomat and the genuine creator of the dynasty, but his brutal disposition overshadowed his accomplishments.

Al-Mahdi and His Sons (775–785)

Al-Mahdi (775-785 CE) was a very different person from his father al-Mansur – whilst his adversaries were never spared on the battlefield, his kindness to his people had no boundaries. He did all in his ability to undo his father’s wrongdoings, releasing their prisoners with honour and lavishing them with his money as restitution for their losses. The love of his life, Al-Khayzuran (d. 789 CE), was a slave girl whom he rescued and elevated to the title of queen.

`In 782 CE, al-Mahdi sent his son, the future Harun al-Rashid, to punish the armies of Empress Irene (r. 780-790 CE). The Byzantines were obliged to come to a peaceful resolution after suffering severe defeats on the field and being cowed in their fortresses. The Caliph, however, did not survive long enough to appreciate his accomplishments; he was poisoned by a concubine and was replaced by his eldest son, al-Hadi (r. 785-786 CE), who was to be followed by Harun, another son of Al-Khayzuran.

Al-Hadi, on the other hand, did not feel bound by his father’s agreement and publicly proclaimed his intention to pass on the throne to his sons. He also disliked his mother’s powerful position among the ministers and tried everything he could to undercut her authority even poisoning her. However, as destiny would have it, the young king perished in his prime. Some believe he developed an incurable sickness, while others believe his death at such a critical juncture was just too coincidental for so many individuals to be a coincidence. The circumstances surrounding his departure from this world are the subject of endless discussion and conjecture.

The Golden Age (775–861)

The Abbasid leadership had to work hard in the final half of the eighth century (750-800) beneath multiple capable caliphs and their courtiers to bring in the administration adjustments required to maintain the discipline of the political issues presented by the empire’s vastness and restricted communications. It was also throughout this early time of the dynasty, namely under the leadership of Al-Mansur, Harun al-Rashid, and al-Ma’mun, that the dynasty’s prestige and strength were established. The war with the Byzantines was revived by Al-Mahdi, and his sons maintained the struggle until Emperor Irene pressed for peace. Nikephoros I breached the contract after many years of calm, then managed to fend off so many assaults throughout the first half of the ninth century. These raids extended into the Taurus Mountains, ending in Rashid’s victory at the Battle of Krasos and the enormous conquest of 806.

Rashid’s fleet was equally successful, capturing Cyprus. Rashid chose to concentrate on Rafi ibn al-insurrection Layth’s in Khorasan and perished there. [39] Whereas the Byzantine Empire was opposing Abbasid dominance in Syria and Anatolia, the caliphate’s military activities were minor, with the attention moving entirely to domestic concerns; Abbasid governors exercised more autonomy and, utilising this growing power, started to establish their offices hereditary. At the same time, the Abbasids faced domestic issues. Harun al-Rashid turned on and executed the majority of the Barmakids, a Persian family that had risen to prominence in governmental positions. [40] Several groups started to flee the empire for other regions or to assume control of remote sections of the empire around the same time. Nonetheless, the reign of al-Rashid and his sons were regarded as the pinnacle of the Abbasids.

After Rashid’s death, the empire was divided by a civil war between both the caliph al-Amin and his brother al-Ma’mun, who had Khorasan’s allegiance. This battle finished with a two-year siege of Baghdad and Al-death Amin in 813. Al-Ma’mun reigned for 20 decades of relative peace, interrupted by a Khurramite insurrection in Azerbaijan, which was sponsored by the Byzantines. Al-Ma’mun was also in charge of establishing an independent Khorasan and repelling Byzantine incursions. Al-Mu’tasim came to power in 833, and his reign led to the end of the powerful caliphs. He bolstered his private army with Turkish soldiers and soon re-entered the Byzantine battle. Though his effort to conquer Constantinople was thwarted because his army was wrecked by a storm, his military adventures were largely successful, ending in a decisive win in the Sack of Amorium. The Byzantines retaliated by attacking Damietta in Egypt, and Al-Mutawakkil retaliated by sending his men back into Anatolia, ravaging and raiding until they were defeated in 863.

Loss of Authority

Following al-death, Ma’mun’s Abbasids experienced a protracted period of ethical and geographical deterioration. Ma’mun’s closest successors refused to live up to the enormous duty thrust given them; al-Mu’tasim (r. 833-842 CE) and al-Wathik (r. 842-847 CE) allowed their Turkish guards to wield power over the state. When al-Mutawakkil (r. 847-861 CE) was killed as a result of a judicial revolt orchestrated by the Turks, it was the last nail in the coffin of Abbasid supremacy. Although al-Mutawakkil was a renowned figure known as “the Nero of the Arabs,” his killing allowed the Turks unparalleled control over his son al-Muntasir (r. 861-862 CE), who had been installed as a slave on the crown. Unfortunately, the young monarch died soon after.

In 909 CE, the Fatimids, the heirs of Fatima, the Prophet’s daughter, emerged as a competing radicalised Shia (anti-Caliphate). They swept out the Aghlabids who had pledged Baghdad homage and started expanding their power. The Fatimids ultimately expanded their dominance over Egypt and even the Hejaz area, which encompassed Mecca and Medina; their prayers were repeated in the holiest of Islamic locations. The Umayyad Emirate of Córdoba proclaimed itself a caliph in 929 CE.

The worst disgrace for the Abbas family, who were Sunnis themselves, would come from another Shia faction: the Buyids. Ali ibn Buya (c. 891-949 CE) founded the famous Iranian-based Shia dynasty, which seized Baghdad from the Abbasids in 945 CE. The only difference for the Abbasids was the group tugging their strings, and their dominion was splitting apart as various provincial rulers proclaimed freedom in a snowball incident. In a famous example of a historic cliche, barbarians from the Central Asian plains arrived to decimate the Buyids. The Seljuk Turks pushed through enormous swaths of the country, from Central Asia to Anatolia, and in 1055 CE, Tughril Beg – a son of Sultan Seljuk – conquered Baghdad; the Buyids were ejected from the city, but the caliphs were merely transferred from one juggler to another.

The Crusade (1095 – 1291)

The Seljuks looked to be an impossible challenge as the 11th century CE continued, but as it concluded, they weren’t any longer the powerful and fearsome power they had already been. The Seljuks were fractured and incapable of resisting European lords when they first landed in the Holy Land in 1096 CE. The Abbasids, ostensibly the rulers of the Muslim ummah (society), were helpless onlookers, while the Seljuks simply drew back from the conflict.

Saladin and one battle flag, Jihad, were about to invert the glorious state of things in Egypt (Fatimids) and the Holy Land (Crusaders). Saladin (1137-1193 CE) was a Sunni devotional leader who became well-known in Egypt in 1169 CE, overthrew Fatimid control in 1171 CE, and returned the old Fatimid domains to Abbasid suzerainty. He resurrected the Muslim cause in the Holy Land and committed his whole life to fight the Crusaders and their supporters in the Islamic holy war. In 1187 CE, he won a tremendous victory in the Battle of Hattin, defeating the majority of the Latin army. Even after his demise, the Crusaders never recovered their former power, and they were finally forced to evacuate Acre, their last refuge in the Holy Land, in 1291 CE by a new Egyptian Muslim army, the Mamluk Sultanate (1250-1517 CE).

The Abbasids were restoring military and temporal dominance in the background of the Crusades. Caliph al-Mustarshid (r. 1092-1135 CE), who began constructing a private dynasty army, was the leader in command of this huge effort and was also slain by the Seljuks in the meantime. Al-Muktafi (r. 1136-1160 CE) finished this mission and proclaimed total autonomy for his home. Enraged by this brave move, the Seljuks attacked Baghdad in 1157 CE, but the city stood fast, and the Turks were forced to flee from the walls after numerous futile attempts. Al-Nasir (d. 1225 CE) is also notable for his administration prowess and for restoring the Abbasids’ dignity by expanding his power far beyond the boundaries of his city to Mesopotamia and portions of Persia; historians see him as the last successful Abbasid emperor.

Baghdad’s Collapse and Its Repercussions (1206–1258)

This newly gained freedom was challenged by a new power, ironically from Central Asia: the Mongols, who had been transformed into a formidable army by Genghis Khan in 1206 CE. The last nominal caliph, al-Must’asim (r. 1242-1258 CE), committed a horrible mistake by breaking much of his military and then accepting Hulegu Khan’s challenge. The main cause for such a stupid decision is debatable; what is obvious is that the Caliph expected military help from all parts of Islam; what he did not realise was that all Muslim rulers were engaged with their concerns.

In 1258 CE, Mongol armies surrounded Baghdad, and in classic Mongol tradition, the whole city including huge stone buildings such as the famed Bayt al-Hikma – was destroyed and its complete inhabitants murdered. The Caliph was wrapped in a rug and crushed by horse hooves. Except for one son who was transferred to Mongolia and one princess who became a slave in Hulegu’s harem, the majority of the royal family was slaughtered. The Mamluk Sultanate halted the Mongol march into Islam’s core at the Battle of Ain Jalut (1260 CE). The Mamluks then established a dynasty of Abbasids as shadow caliphs in Cairo, although these individuals were only symbolic. Sultan Selim I of the Ottoman Sultanate (1299-1924 CE) captured the Mamluk kingdoms in 1517 CE and bestowed the caliphal title on his family.

Abbasid’s After-Fall

The Abbasid disinformation campaign against the Umayyads was exceedingly effective, yet the Abbasids continued with the same government reforms that had earned them popularity against the Umayyads. After deposing the governing party, the Abbasids took charge of a smaller realm than their ancestors, since Spain had been lost forever; the disintegration of the Islamic empire began with the emergence of the Abbasids, not later as most people think. The Abbasids had no desire to expand wider; in fact, they attempted to cooperate with European powers against their shared opponent, the Emirate of Córdoba.

Because many Abbasid monarchs were not born politicians, they started to depend on individuals to govern the kingdom. Cracks that had begun to form in the Arab-dominant structure during the reign of al-Ma’mun, who was pro-Persian (his mother was Persian), became divisions with his death when the dynasty was forced to serve other parties. The attempts of successive caliphs to restore the Abbasids’ power are admirable, but every person and everything surrounding them was always against them. The invasion of Baghdad signalled the end of the once-mighty empire. Their legacy lives on in the shape of sharia (Islamic law) and the modern era as we know it today, thanks to their encouragement of all kinds of arts, scholarship, and, most notably, scientific study into natural phenomena.

Read Less